Expanding horizons to find solutions to child poverty in Finland: what can we learn from other countries?

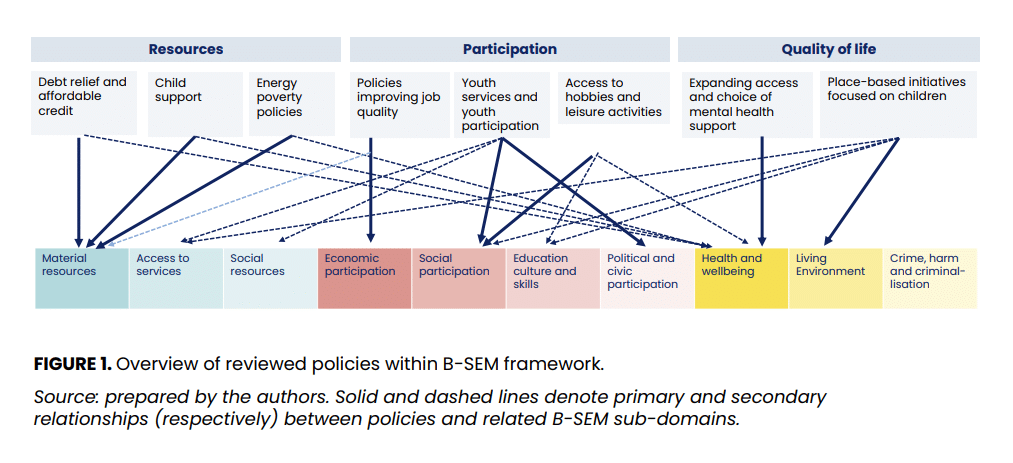

Tackling child poverty, understood as “economic, social and emotional deprivation, leaving children unable to fulfil their rights, participate or achieve their full potential” (UNICEF, 2022) means looking beyond the narrow perspective of income and material resources. This is why we considered a broader spectrum of policies, covering nine policy areas related to resources, participation and quality of life.

Here are some key insights emerging from our review and some of the country case studies discussed.

In many areas, Finland is doing well by international standards but a greater focus on some especially vulnerable groups is needed

Finland has had a longer experience than other countries with improving service integration, something that is found to be important to improve access to mental health services. Examples from New Zealand are instructive in showing how, in order to reach minority groups, effort is required to involve these communities in the design and delivery of primary services along with investment in workforce development.

In relation to improving access to hobbies, recent developments in Finland are promising as they build on local preferences and bottom-up engagement. Examples from the Netherlands show that positive results can come from targeting some disadvantaged groups to complement universal provision.

In some areas, there are clear policy gaps and opportunities for improvement

Finland lacks specific debt relief schemes for LILA (Low-Income Low-Asset) or NINA (No-Income No Asset) debtors. Schemes adopted in some other countries, such as New Zealand, show that they can provide a fresh start and alleviate the hardship experienced by vulnerable families and prevent further spiralling into debt.

Child support (maintenance payments received from a non-resident parent) can be a significant source of income for lone parent families. The Finnish system has some positive features (such as guaranteed advances) but including the value of any child support payments in the calculation of eligibility for means-tested benefits reduces their impact on poverty alleviation. In other countries, child support is not taken into account in the social security system when it comes to assessing eligibility and as a result has a greater poverty reducing potential.

Some effective solutions require long-term, society-wide change

For instance, the Netherlands succeeds at securing high-quality part-time work, which can help to reduce poverty risks especially among families with greater care commitments. Improving the quality of part-time work requires not just regulation but a long-term collaboration across different civil society actors, the public and the private sector.

Improving low-income households’ access to credit requires solutions suited to the Finnish credit sector and there is no quick fix. There are however some small-scale solutions. In countries such as the UK, Canada, Ireland or New Zealand, social lending, for instance through credit unions or community financial institutions, has been shown to help reach financially excluded groups such as migrants and ethnic minorities.

The evidence base is not always rich in some policy areas, but the need to develop solutions specific to the Finnish context is pressing

Concerns about in-work poverty underpin efforts in many countries to tackle precarious employment. Examples from Belgium show how cooperatives and third sector actors can play an important role in increasing access to social security, opening up opportunities for collective bargaining and influence regulation for self-employed, ’gig economy’ or platform workers.

Place-based approaches are not common in Finland but they can, especially through participatory approaches and community-led development, help to respond to local needs in face of increased geographical concentration of poverty and disadvantage.

These lessons highlight both strengths and weaknesses of the present policy context in Finland and offer useful insights to develop a sustainable strategy to tackle child poverty in a multidimensional perspective and improve children’s material, social and emotional wellbeing.

Kirjoittaja

Irene Bucelli

Research fellow, London School of Economics and Political Science